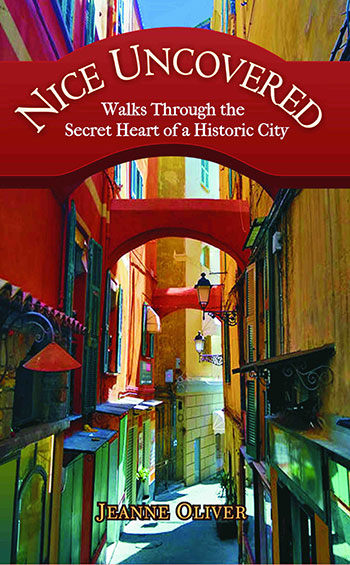

Think of Nice and images of the glistening Mediterranean bordering the iconic Promenade des Anglais swim into view. Less well-known are the many sites and neighborhoods that achieved UNESCO World Heritage status in July 2021. According to UNESCO, Nice “reflects the development of a city devoted to winter tourism, making the most of its mild climate and its coastal situation, between sea and mountains.” Jeanne Oliver, author of Nice Uncovered: Walks Through the Secret Heart of a Historic City, explores the tourist heritage of Nice…

UNESCO-listed “Nice Winter Resort Town of the Riviera”

Tourism has defined the development of Nice for well over 200 years. And it’s this that has seen UNESCO recognise the “Outstanding Universal Value” of Nice’s heritage in terms of architecture, landscape and urban planning, and an area of 522 hectares shaped by the cosmopolitan winter resort which has resulted in a spectacular fusion of international cultural influences.

The first tourist was arguably Scotsman Tobias Smollett who praised Nice in his bestseller Travels Through France and Italy published in 1766. His British readers were intrigued and began visiting Nice in the late 18th century. They first settled on the land west of Cours Saleya, which opened for development after the town walls were destroyed in 1706. Rue François de Paule was considered chic even before the Opera was built in the late 19th century.

By the beginning of the 19th century the trickle of British visitors turned into a steady stream. They fanned out to what is now the Carré d’Or and clustered in a community around the Croix de Marbre. Stores selling products from home sprouted up in the neighborhood they called “Newborough”.

How Nice developed due to tourists

These early Brits avoided the crowded, dirty streets of the Old Town but they liked to stroll the rue des Ponchettes which bordered the square Cours Saleya which was turned into a garden promenade. However, to access the walkways, they had to cross a bridge which spanned the Paillon river and then make their way through the Old Town. In 1822 the Reverend Lewis Way of Nice’s new Anglican Church raised money to construct a path along the sea, easily accessible from their neighborhood. The path, Chemin des Anglais, was completed in 1824. It reached from the western banks of the Paillon river to rue Meyerbeer. Over the course of the 19th century, it was extended west and eventually became the Promenade des Anglais.

A stroll west along the Promenade reveals spectacular examples of Belle Epoque architecture. The Villa Masséna, now the Masséna Museum, is a fine example of a private villa on the Promenade, while the Hotel Negresco heads a procession of elegant 19th century hotels.

Nice’s 19th-century rulers, the Dukes of Savoy, quickly recognized the potential of the “distinguished foreign visitors” which included Russians, Germans, and Americans. From the mid-19th century onward, every urbanization decision taken was aimed at increasing the comfort and enjoyment of holidaymakers. Foreign tourists liked exotic vegetation? Let’s plant the Promenade des Anglais with palm trees! Foreign tourists liked gardens? The Jardin Albert 1er became a 19th-century seaside park, while the ruins of the old Colline du Chateau became a hilltop park with sea views.

Architectural style

The opening of the Nice train station in 1864 shortly after Nice became part of France in 1860, sparked the development of the Quartier des Musiciens. Boulevard Victor Hugo was the first street to be laid out and the rest followed in a grid pattern. Fabulous Belle Epoque residences such as the Palais Baréty were followed by a new style, Art Deco, in the interwar period.

The verdant hill of Cimiez already had a few Belle Epoque hotels even before Queen Victoria chose the Excelsior Regina Hotel as her preferred holiday spot in 1895. Within a decade the entire neighborhood was transformed from farmland to a playground for European nobility. The stately apartment buildings now lining the Boulevard de Cimiez were designed as hotels and followed contemporary tastes. When Orientalism came into vogue at the turn of the 20th century, minarets were chosen to adorn the Hotel Alhambra.

Another neighborhood favored by 19th-century Brits was Mont Boron, the hill between Nice and Villefranche-sur-Mer. In 1891 they founded the l’Association Des Amis Des Arbres to protect trees and wooded areas against over-development. The Chateau de l’Anglais, built by Colonel Robert Smith was inspired by his tour of duty in India and brings a touch of exoticism to this forested hill.

Just as the British aristocracy congregated in Cimiez and Mont Boron, the Russian aristocracy followed Tsar Alexander II to the Piol neighborhood after he wintered there in 1864. The Russian Orthodox Cathedral of Saint Nicholas, consecrated in 1912, testifies to the long Russian presence in Nice.

A world famous heritage site

The only part of the more than 500-hectare UNESCO-protected area that had little to do with tourism development is Port Lympia. It was vital to Nice’s export trade however and most of it does date from the late 19th-century.

Nice’s World Heritage designated area covers almost all the city’s highlights except for one surprising omission. The winding streets of Vieux Nice north of Cours Saleya are not UNESCO listed. Most of the baroque churches and pastel buildings date from the 18th century and thus are before Nice’s development as a tourist destination.

Jeanne Oliver is a travel writer who lives in Nice. She is the author of Nice Uncovered: Walks through the Secret Heart of a Historic City. Find out more at jeanneoliver.net